When Admitted to the Hospital for Myasthenia Gravis

In case you missed it, check out parts 1 and 2 of this series:

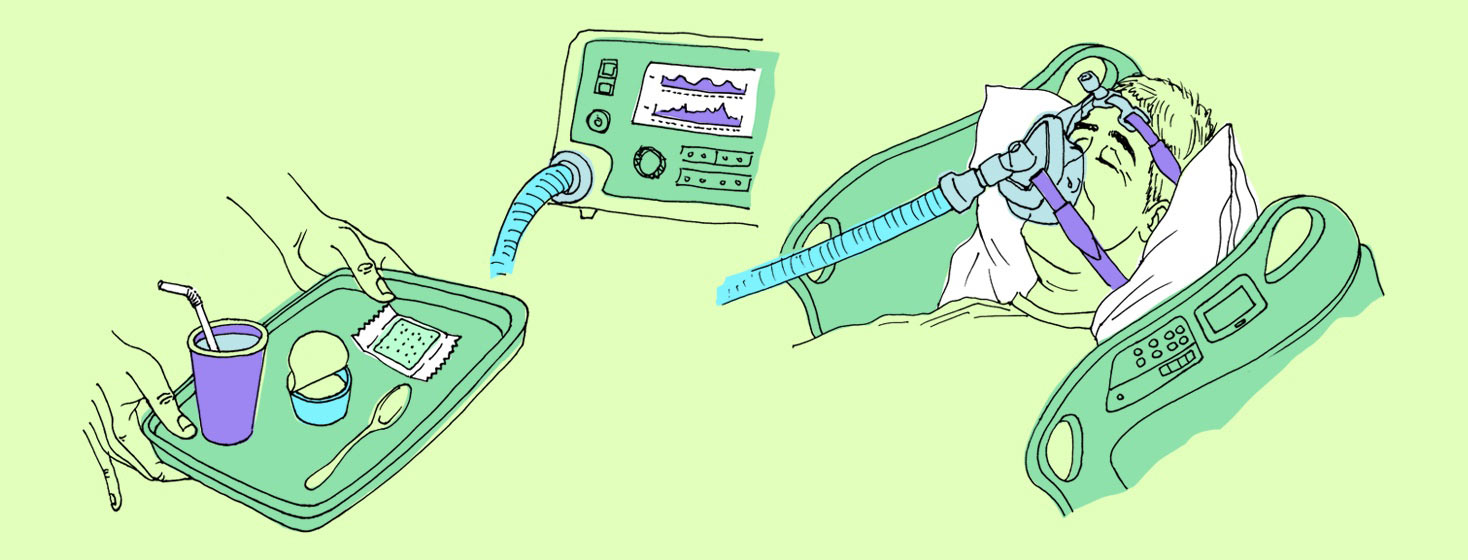

When a myasthenia gravis exacerbation is severe, a hospital stay may be on the agenda. Some people become too weak to walk, sit up, or even move around in bed. Some have such severe swallowing issues that they can’t eat or drink at all and must be on a feeding tube.1

In the worst cases, when an exacerbation causes severe respiratory muscle weakness, patients may have to be placed on a BiPAP (bi-level positive airway pressure) machine or intubated and put on a ventilator until treatment controls the flare.2,3

I’m lucky; while I’ve had to be hospitalized and placed on BiPAP due to my myasthenia gravis (MG) multiple times, I’ve never been intubated. Here’s what a typical hospital stay looks like for me.

Starting treatment for my MG exacerbation

It starts in the emergency room, where once it’s been decided I need to be admitted, I’ll be seen by a hospitalist and the neurologist on call. I’ll usually be on BiPAP and sometimes oxygen, and have IV fluids running.

Since I respond well to intravenous immune globulin (IVIG), the plan is usually to start a multi-day course as soon as possible.

If there is a long wait for a hospital bed, they will sometimes start treatment while I’m still in the ER. If I have an underlying infection, I’ll also be started on IV antibiotics.

Closely monitored

Then I’m moved to either the ICU or the stepdown unit, where I can be on continuous heart and respiratory monitors, and watched closely by nurses.

MG flares can be dangerous because breathing can go downhill quickly, so close monitoring is essential.

A respiratory therapist takes care of my BiPAP and oxygen. They will check my Negative Inspiratory Force (NIF) and my Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) every 4 hours.

Measuring my breathing

NIF is measured with a small meter that requires you to inhale against resistance. It measures how strong your diaphragm is. In my experience, when my NIF is under 40, that’s a warning sign of respiratory failure. I've been told that a NIF under 20 will usually get you intubated.

FVC is a different meter that measures how much air you can blow out in a single breath. It measures respiratory muscle strength. When I’m initially hospitalized my FVC is usually about 45–50 percent of what’s predicted for someone of my age and height. My NIF is usually in the 30s or 40s.

Seeing a speech therapist

The hospitalist makes a determination about what diet they feel is safe for me. Since I have problems chewing and swallowing during an exacerbation, it’s often left to a speech therapist to make the final assessment.

I may be designated NPO (nothing-by-mouth) until that assessment. If that happens, I usually try to make a case to be allowed very limited ice chips to keep my tongue moist. The speech therapist will give me a variety of things to try, and watch me swallow to see if I cough or the food gets stuck.

We’ll try water, thickened juice, apple sauce, pudding, cheese, and on up to crackers if I’m doing really well. At first, when I’m in a bad flare, I usually cough on water and can’t manage anything more than apple sauce. So I’ll be put on a purée diet, sometimes with thickened liquids.

Additional support

A harsh reality: because I’m so weak and usually can’t stand, let alone walk, I’ll have a bedside commode for toileting. It’s not exactly dignified, but it’s far easier for me than trying to use a bedpan or bed-urinal.

I’ll need assistance from one or sometimes 2 nurses to get on and off the commode and clean myself. When I’m at my weakest, I can’t even move myself in bed, and have to be repositioned periodically by my nurses to prevent bedsores.

Recovery time

Once the treatment starts to work and I start getting a little strength back, usually after 2 to 3 days, I’ll also be seen by a physical therapist and an occupational therapist, who assess my ability to stand, walk, and care for myself.

At first, I can do none of those things. My criteria for being able to go home from the hospital are usually being able to walk with my forearm crutches at least 10 feet (3 meters), transfer to and from my wheelchair, and do minimal self-care, like going to the toilet on my own.

If I’m having a slow recovery, once my breathing is no longer severely compromised, I may have to spend a few weeks in an acute skilled nursing facility (SNF) before I’m recovered enough to go home.

Home health care

Once I’m home, I’ll have home health care for a few weeks. I’ll have a bath aide to help me bathe once a week, and I’ll see a speech therapist to monitor and assess my swallowing and help me know when it’s safe to advance my diet.

I’ll also see a physical therapist who will help me regain strength and mobility while being careful not to worsen the exacerbation, and sometimes an occupational therapist to help with modifications to my house and routines to conserve energy.

My hospital stays usually last about a week, and it usually takes a few weeks to get back to my baseline after a big flare. Patience during convalescence at home is key; and no matter how bored I am, rest, rest, rest.

Join the conversation